The Story:

from the Wall Street Journal:

Ten Days That Changed Capitalism

By DAVID WESSEL

March 27, 2008

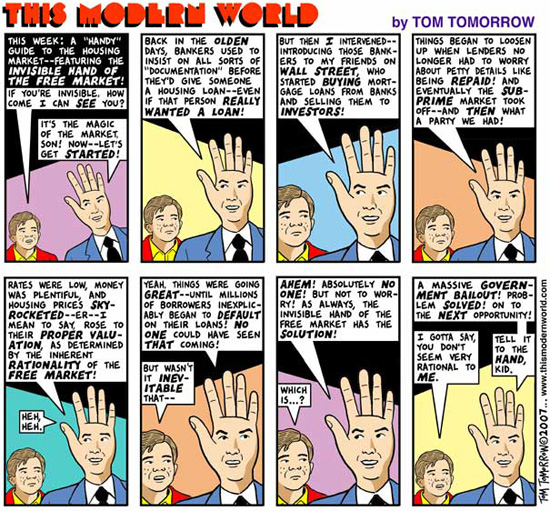

The past 10 days will be remembered as the time the U.S. government discarded a half-century of rules to save American financial capitalism from collapse.

On the Richter scale of government activism, the government’s recent actions don’t (yet) register at FDR levels. They are shrouded in technicalities and buried in a pile of new acronyms.

But something big just happened. It happened without an explicit vote by Congress. And, though the Treasury hasn’t cut any checks for housing or Wall Street rescues, billions of dollars of taxpayer money were put at risk. A Republican administration, not eager to be viewed as the second coming of the Hoover administration, showed it no longer believes the market can sort out the mess.

“The Government of Last Resort is working with the Lender of Last Resort to shore up the housing and credit markets to avoid Great Depression II,” economist Ed Yardeni wrote to clients.

First, over St. Patrick’s Day weekend, the Fed (aka the Lender of Last Resort) and the Treasury forced the sale of Bear Stearns, the fifth-largest U.S. investment bank, to J.P. Morgan Chase at a price so low that a shareholder rebellion prompted J.P. Morgan to raise the price. To induce J.P. Morgan to do the deal, the Fed agreed to take losses or gains, if any, on up to $29 billion of securities in Bear Stearns’s portfolio. The outcome will influence the sum the Fed turns over to the Treasury, so this is taxpayer money; that’s why the Fed sought Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson’s OK.

Then the Fed lent directly to Wall Street securities firms for the first time. Until now, the Fed has lent directly only to Main Street banks, those that take deposits from ordinary folks. That’s because banks were viewed as playing a unique economic role and, supposedly, were more closely regulated than other types of lenders. In the first three days of this new era, securities firms borrowed an average of $31.3 billion a day from the Fed. That’s not small change, and it’s why Mr. Paulson, after the fact, is endorsing changes to give the Fed more access to these firms’ books.

http://online.wsj.com/article/SB120657397294066915.html?mod=yhoofront

The Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act, also known as the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Financial Services Modernization Act, Nov. 12, 1999, is an Act of the United States Congress which repealed the Glass-Steagall Act, opening up competition among banks, securities companies and insurance companies. The Glass-Steagall Act prohibited a bank from offering investment, commercial banking, and insurance services.

The Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act allowed commercial and investment banks to consolidate. For example, Citibank merged with Travelers Group, an insurance company, and in 1997 formed the conglomerate Citigroup, a corporation combining banking and insurance underwriting services. Other major mergers in the financial sector had already taken place such as the Smith-Barney, Shearson, Primerica and Travelers Insurance Corporation combination in the mid-1990’s. This combination, announced in 1993 and finalized in 1994, would have violated the Glass-Steagall Act and the Bank Holding Acts by combining insurance and securities companies, if not for a temporary waiver process. The law was passed to legalize these mergers on a permanent basis.

and now, a word from our sponsors:

Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (S. 900): A Major Step Toward Financial Deregulation

by David C. John

October 28, 1999

Congress may soon have an opportunity to officially recognize that America’s financial services industry has changed over the past 66 years. It will consider the conference report to a bill, known as the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (S. 900), which would repeal obsolete Depression-era laws that still govern financial transactions today. Significantly, this means banks, securities firms, and other types of financial institutions could join together to offer their customers a more complete range of services.

THE CHANGING REALM OF FINANCIAL SERVICES

Since 1933, federal law has effectively divided the U.S. financial services industry into separate and distinct types of institutions, such as banks, mutual funds managers, insurance companies, and securities firms. For the most part, the separate types of financial services companies were strictly prohibited from merging and from offering their products. Thus, banks were not allowed to own securities firms or to underwrite or sell most stocks and bonds. Similarly, insurance companies were prohibited from owning banks or taking deposits. Each type of firm had its own regulatory agency that jealously guarded its authority over the companies it supervised. And because deposits are federally insured, strict limitations were placed on the activities of banks.

This artificial division worked for some time but, over the past 20 years, the distinctions between these types of transactions have blurred. Innovative managers and technological advances allowed some firms to offer services that closely resembled those offered by competitors. At the same time, seemingly minor loopholes in the laws were exploited to allow banks to increase their securities activities and permit securities houses and other types of firms to buy or open companies–known as non-bank banks–that offered credit cards and other banking products. Federal courts ruled that these new activities were legal, but because they were conducted indirectly through legal loopholes, they often became less efficient and more expensive than necessary.

http://www.heritage.org/Research/Regulation/BG1338.cfm

GRAMM’S STATEMENT AT SIGNING CEREMONY

FOR GRAMM-LEACH-BLILEY ACT

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE:

Friday, November 12, 1999

http://banking.senate.gov/prel99/1112gbl.htm

Sen. Phil Gramm, chairman of the Senate Committee on Banking, Housing and Urban Affairs, made the following statement today in a ceremony at the Eisenhower Executive Office Building, where President Clinton signed the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act into law:

“The world changes, and Congress and the laws have to change with it.

“Abraham Lincoln used to like to use the analogy that old and outmoded laws need to be changed because it made about as much sense to continue to impose them on people as it did to ask a man to wear the same clothes he did when he was a child.

“In the 1930s, at the trough of the Depression, when Glass-Steagall became law, it was believed that government was the answer. It was believed that stability and growth came from government overriding the functioning of free markets.

“We are here today to repeal Glass-Steagall because we have learned that government is not the answer. We have learned that freedom and competition are the answers. We have learned that we promote economic growth and we promote stability by having competition and freedom.

“I am proud to be here because this is an important bill; it is a deregulatory bill. I believe that that is the wave of the future, and I am awfully proud to have been a part of making it a reality.”

And guess who the general co-chairman of John McCain’s presidential campaign is?

A little history on the Glass-Steagall act…

from investopedia (Forbes Media):

What Was The Glass-Steagall Act?

by Reem Heakal

In 1933, in the wake of the 1929 stock market crash and during a nationwide commercial bank failure and the Great Depression, two members of Congress put their names on what is known today as the Glass-Steagall Act (GSA). This act separated investment and commercial banking activities. At the time, “improper banking activity”, or what was considered overzealous commercial bank involvement in stock market investment, was deemed the main culprit of the financial crash.

Commercial banks were accused of being too speculative in the pre-Depression era, not only because they were investing their assets but also because they were buying new issues for resale to the public. Thus, banks became greedy, taking on huge risks in the hope of even bigger rewards. Banking itself became sloppy and objectives became blurred. Unsound loans were issued to companies in which the bank had invested, and clients would be encouraged to invest in those same stocks.

Effects of the Act – Creating Barriers

Senator Carter Glass, a former Treasury secretary and the founder of the U.S. Federal Reserve System, was the primary force behind the GSA. Henry Bascom Steagall was a House of Representatives member and chairman of the House Banking and Currency Committee. Steagall agreed to support the act with Glass after an amendment was added permitting bank deposit insurance [The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation – (FDIC)].

As a collective reaction to one of the worst financial crises at the time, the GSA set up a regulatory firewall between commercial and investment bank activities, both of which were curbed and controlled. Banks were given a year to decide on whether they would specialize in commercial or in investment banking. Only 10% of commercial banks’ total income could stem from securities; however an exception allowed commercial banks to underwrite government-issued bonds. Financial giants at the time such as JP Morgan and Company[does this name ring any bells?], which were seen as part of the problem, were directly targeted and forced to cut their services and, hence, a main source of their income. By creating this barrier, the GSA was aiming to prevent the banks’ use of deposits in the case of a failed underwriting job.

http://www.investopedia.com/articles/03/071603.asp

The Financial Crisis, in a nutshell

from:

Testimony of Robert Kuttner before the Committee on Financial Services

U.S. House of Representatives

Washington, D.C.

October 2, 2007

…I [have] devoted a lot of effort to reviewing the abuses of the 1920s, the effort in the 1930s to create a financial system that would prevent repetition of those abuses, and the steady dismantling of the safeguards over the last three decades in the name of free markets and financial innovation.

The Senate Banking Committee, in the celebrated Pecora Hearings of 1933 and 1934, laid the groundwork for the modern edifice of financial regulation. I suspect that they would be appalled at the parallels between the systemic risks of the 1920s and many of the modern practices that have been permitted to seep back in to our financial markets.

Although the particulars are different, my reading of financial history suggests that the abuses and risks are all too similar and enduring. When you strip them down to their essence, they are variations on a few hardy perennials – excessive leveraging, misrepresentation, insider conflicts of interest, non-transparency, and the triumph of engineered euphoria over evidence.

The most basic and alarming parallel is the creation of asset bubbles, in which the purveyors of securities use very high leverage; the securities are sold to the public or to specialized funds with underlying collateral of uncertain value; and financial middlemen extract exorbitant returns at the expense of the real economy. This was the essence of the abuse of public utilities stock pyramids in the 1920s, where multi-layered holding companies allowed securities to be watered down, to the point where the real collateral was worth just a few cents on the dollar, and returns were diverted from operating companies and ratepayers. This only became exposed when the bubble burst. As Warren Buffett famously put it, you never know who is swimming naked until the tide goes out.

There is good evidence–and I will add to the record a paper on this subject by the Federal Reserve staff economists Dean Maki and Michael Palumbo–that even much of the boom of the late 1990s was built substantially on asset bubbles. [Disentangling the Wealth Effect: a Cohort Analysis of Household Savings in the 1990s]

A third parallel is the excessive use of leverage. In the 1920s, not only were there pervasive stock-watering schemes, but there was no limit on margin. If you thought the market was just going up forever, you could borrow most of the cost of your investment, via loans conveniently provided by your stockbroker. It worked well on the upside. When it didn’t work so well on the downside, Congress subsequently imposed margin limits. But anybody who knows anything about derivatives or hedge funds knows that margin limits are for little people. High rollers, with credit derivatives, can use leverage at ratios of ten to one, or a hundred to one, limited only by their self confidence and taste for risk. Private equity, which might be better named private debt, gets its astronomically high rate of return on equity capital, through the use of borrowed money. The equity is fairly small. As in the 1920s, the game continues only as long as asset prices continue to inflate; and all the leverage contributes to the asset inflation, conveniently creating higher priced collateral against which to borrow even more money.

A last parallel is ideological — the nearly universal conviction, 80 years ago and today, that markets are so perfectly self-regulating that government’s main job is to protect property rights, and otherwise just get out of the way.

We all know the history. The regulatory reforms of the New Deal saved capitalism from its own self-cannibalizing instincts, and a reliable, transparent and regulated financial economy went on to anchor an unprecedented boom in the real economy. Financial markets were restored to their appropriate role as servants of the real economy, rather than masters. Financial regulation was pro-efficiency. I want to repeat that, because it is so utterly unfashionable, but it is well documented by economic history. Financial regulation was pro-efficiency. America’s squeaky clean, transparent, reliable financial markets were the envy of the world. They undergirded the entrepreneurship and dynamism in the rest of the economy.

Beginning in the late 1970s, the beneficial effect of financial regulations has either been deliberately weakened by public policy, or has been overwhelmed by innovations not anticipated by the New Deal regulatory schema. New-Deal-era has become a term of abuse.

Of course, there are some important differences between the economy of the 1920s, and the one that began in the deregulatory era that dates to the late 1970s. The economy did not crash in 1987 with the stock market, or in 2000-01. Among the reasons are the existence of federal breakwaters such as deposit insurance, and the stabilizing influence of public spending, now nearly one dollar in three counting federal, state, and local public outlay, which limits collapses of private demand.

And, what happened in the late 1970s and the 1980s? The Reagan Revolution, which first announced itself with the heavily bankrolled “Taxpayer Revolt”, passing Proposition 13, which drastically slashed, and permanently capped taxes on property owners– and while providing much-needed tax relief for middle-class homeowners– benefited commercial property owners even more, and created a steadily increasing shortfall of revenues to schools and other state services. Another key component of the Reagan platform: deregulation.

Three memorable results of this era: the junk bond debacle, the Savings and Loan Collapse, and the stock market crash of 1987:

from stock-market-crash.net:

The stock market crash of 1987 was the largest one day stock market crash in history. The Dow lost 22.6% of its value or $500 billion dollars on October 19 th 1987! In order to understand the crash, we must first study the cause.

1986 and 1987 were banner years for the stock market. These years were an extension of an extremely powerful bull market that started in the summer of 1982. This bull market had been fueled by hostile takeovers, leveraged buyouts and merger mania. Companies were scrambling to raise capital to buy each other out, in essence. The philosophy of the time was that companies would grow exponentially simply by constantly purchasing other companies. In leveraged buyouts, a company would raise massive amounts of capital by selling junk bonds to the public. Junk bonds are simply bonds that have a high risk of loss, so they pay a high interest rate. The money raised by selling junk bonds, would go towards the purchase of the desired company.

One familiar name from the S & L crisis: Neil Bush of Silverado Savings and Loan

from the Washington Post

In 1985 [Neil Bush] joined the board of Silverado Savings and Loan, which had already lent millions to Walters and Good. Over the next three years, Silverado lent an additional $106 million to Walters and $35 million to Good, although the two men’s real estate empires were collapsing.

Good used some of that money to buy JNB, although it was still losing money. He raised Bush’s salary to $120,000 and awarded him a bonus of $22,000. He also hired Bush as a director of one of his companies, at a salary of $100,000.

Neither Good nor Walters ever repaid a nickel of their Silverado loans, and in 1988 Silverado went belly up, leaving U.S. taxpayers holding the bag for $1.3 billion in debts.

Picking through the wreckage, regulators from the federal Office of Thrift Supervision concluded in 1991 that Bush’s deals with Good and Walters while serving on Silverado’s board constituted “multiple conflicts of interest.” Bush became a public symbol of the $500 billion savings and loan scandal. Protesters picketed his home and pasted mock wanted posters around Washington: “Jail Neil Bush.”

Bush proclaimed his innocence, declaring at a news conference that “self-serving regulators” were persecuting him because he was the president’s son. But when he appeared before the House Banking Committee in 1990, he admitted that some of his deals looked “a little fishy.”

Ultimately, Bush paid $50,000 as his part of a federal lawsuit against Silverado and was reprimanded by the OTS. Good and Walters ended up declaring bankruptcy, and JNB, which had never found oil or made money, quietly perished.

Today, Bush maintains that he did nothing wrong.

from rationalrevolution.net:

There are several ways in which the Bush family plays into the Savings and Loan scandal, which involves not only many members of the Bush family but also many other politicians that are still in office and still part of the Bush Jr. administration today. Jeb Bush, George Bush Sr., and his son Neil Bush have all been implicated in the Savings and Loan Scandal, which cost American tax payers over $1.4 TRILLION dollars (note that this is about one quarter of our national debt).

Between 1981 and 1989, when George Bush finally announced that there was a Savings and Loan Crisis to the world, the Reagan/Bush administration worked to cover up Savings and Loan problems by reducing the number and depth of examinations required of S&Ls as well as attacking political opponents who were sounding early alarms about the S&L industry. Industry insiders were aware of significant S&L problems as early 1986 that they felt would require a bailout. This information was kept from the media until after Bush had won the 1988 elections.

Jeb Bush defaulted on a $4.56 million loan from Broward Federal Savings in Sunrise, Florida. After federal regulators closed the S&L, the office building that Jeb used the $4.56 million to finance was reappraised by the regulators at $500,000, which Bush and his partners paid. The taxpayers had to pay back the remaining 4 million plus dollars.

Neil Bush was the most widely targeted member of the Bush family by the press in the S&L scandal. Neil became director of Silverado Savings and Loan at the age of 30 in 1985. Three years later the institution was belly up at a cost of $1.6 billion to tax payers to bail out.